The Underrated Art of Translation

|

| Joohee Yoon via The New Yorker. |

The history of literary translation can be traced back at least to the Roman Empire, when writers and scholars began translating Greek works into Latin, such as tragedies for travelling companies to perform or philosophical reflections to study. However, to understand the depth and importance of translation, it is fundamental to talk about the most influential book of all time: the Bible.

|

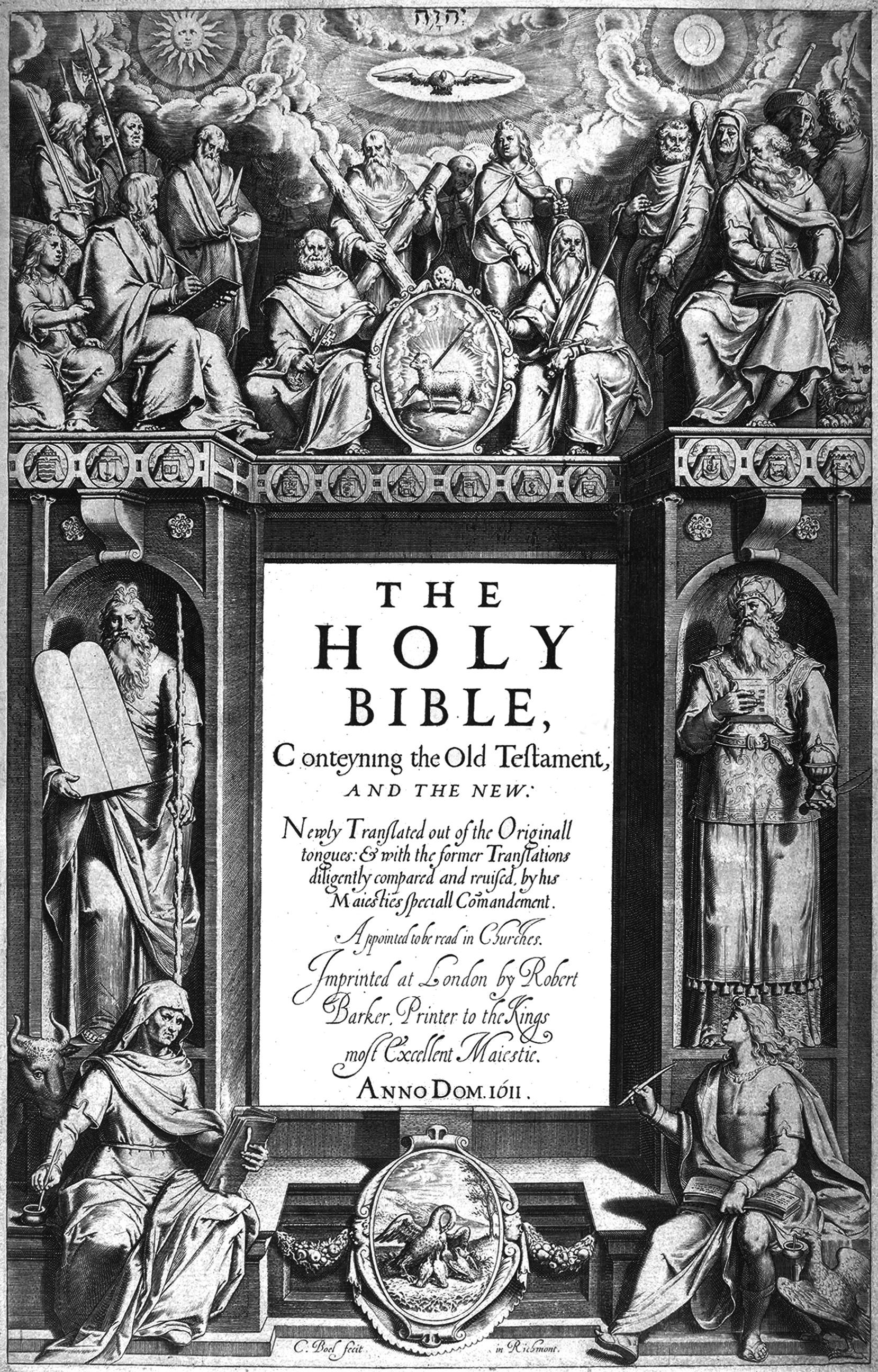

| Via Wikimedia. |

The earliest translation of the Hebrew Bible was the Septuagint, a Greek translation said to have been translated with the exact same wording by 70 different translators, which surely meant it was Holy. In the year 382 a.d., Saint Jerome was tasked with the Latin translation of the Bible. He chose to translate the original text instead of the Septuagint, claiming that the Greek version was not easy to read or understand for the commoners. This sparked debate from clergy authorities, who insisted that the Septuagint was the true word of God and its phrasing should be respected. Intended on translating not word for word but conveying the true meaning and intent of the text in a new vernacular, Saint Jerome persisted and wrote the Vulgate, which eventually superseded the Septuagint as the official text because it was more comprehensible and accesible to read for the common folk. Centuries later, King James I of England set to do exactly what Saint Jerome did, translating the Bible with the goal of reproducing the beauty of the language, bringing it to the common worshiper. In this process, many English expressions where created, most of which are still used to the day, for example:

"[To be] at their wit's end",

"An eye for an eye", and

"Two are better than one".

See, it's not just about finding a word that is equivalent to the foreign word. It is not enough to know the language. The translator must understand the purpose, style and context of the writer and build a relationship with them. Whether it is a fully collaborative process or a simple series of e-mails, an author or publisher must trust that the translator will find a balance between faithfulness and accuracy when translating. Of course, this trust comes with its share of risks. A translator may make a choice or take creative liberties that a writer doesn't find agreeable. These liberties can result in mistranslations that can completely change the meaning of the work.

See, it's not just about finding a word that is equivalent to the foreign word. It is not enough to know the language. The translator must understand the purpose, style and context of the writer and build a relationship with them. Whether it is a fully collaborative process or a simple series of e-mails, an author or publisher must trust that the translator will find a balance between faithfulness and accuracy when translating. Of course, this trust comes with its share of risks. A translator may make a choice or take creative liberties that a writer doesn't find agreeable. These liberties can result in mistranslations that can completely change the meaning of the work.

World building and invented words can be particularly challenging because the translator must convey the meaning of the text without equivalent vocabulary. Such is the case of Harry Potter, a fantasy saga that has been translated into over 75 languages. Such range of translation makes it difficult for translators to collaborate directly with the author and the responsibility of conveying a compelling and comprehensible story falls on the translator.

The balance between fidelity and accuracy is threaded differently by every translator. As we now know, these differences have caused controversy ever since the Bible. "Which is the better translation?" is an open-ended question that depends on author, translator and reader. It depends on the kind of concessions each translator makes. Literary translations require creativity, and how assertive a translator's creative inputs are rely strongly on intuition. Not all translators should translate all texts, even very good translators. Some step down from projects because they accept that they may not be the best fit for a book.

Translation often don't age well enough to accept an ultimate "best translation", though. English translations of Russian literature, for example, have a long history of debate among translators and their work.

|

| Via Russia Beyond. |

In 1892, Constance Garnett began her career as a translator after learning Russian during a confined pregnancy. In 1894, she went on a three-month trip to Russia and dined with Tolstoy himself. By the time she retired, she had translated 71 volumes of literature, including all of Dostoevsky's work. She is widely credited with the popularity of Russian literature gained in the 1920's, since she was the pioneer in English translations of such works. However, her work per se was heavily criticized. Her approach to translating was with a focus on the finish line, getting the job done. She would translate a page, lay it on a pile, and not give it a second look. Some of her harshest critics were Russian exiles who claimed that Dostoevsky and Tolstoy were so indistinguishable, that they weren't reading them, they were reading her.

In the 1980's, Richard Pevear and his wife, Russian émigrée Larissa Volokhonsky decided to write their own translation of "The Brothers Karamazov" after Volokhonsky claimed that the David Magarshark's edition was entirely different from Dostoevsky's. From then on, they created a division of labor: Larissa would first write a transcript as specific as possible with notes about the writer's style. Then, Richard would write a smoother English text. They would go back and forth until they landed on a version that felt true to the author, down to motifs and style. Every stumble, every ramble, every trace of clumsiness that the writer showed was transmitted into the Pevear-Volokhonsky translation, because that is how he wrote, how people speak and think, and so the text should reflect that. According to The New Yorker, the couple are the "premier Russian-to-English translators of the era".

In 2005, Anthony Briggs's translation of War & Peace was published. The British academic and professional translator stated in a note to the publication that Tolstoy was an easy read for a Russian and it had been equally easy to translate. Tolstoy wrote his novel in different languages, using mainly French as the preferred language of his aristocrat characters. While Pevear and Volokhonsky translated the French in foot notes (as did the writer and a number of other translators), Briggs translated it within the text. He also spelled out some obscenities that Tolstoy had kept implied as ellipses. To some, Briggs's reflection and translation was welcome, since it brought an unprecedented ease of comprehension to the novel. To others, it was plain treason against Tolstoy. Anthony Briggs's translation was reviewed by The Guardian as accurate and clear, but lacking in fidelity.

Which translation of War & Peace is best? Is it Garnett's pioneering insertion of the text to English speaking readers? Is it Pevear and Volokhonsky's promise of fidelity? Or it is Anthony Briggs's ease and simplification of language? Who's to say?

Writer and translator Mike Polizzotti stated it clearly in an MIT Press Podcast episode:

"Translation is about understanding the deep structure and the underpinnings of what is going on in literary texts, what the author meant to do, how the author did it, how that can be conveyed, what that means in the author's original culture, what the resonances are, what the effect on the reader is; [...] With all those differences you still nonetheless need to make a text that on the other hand represents the effect on the reader the way the original text affected the original reader, and yet at the same time can speak to a reader today in a different culture, a different language, a different context and a different time period."

At the end of the day, translations are perishable items. As times change, so does our world perception. It is through translators that literature can be shared and appreciated across countries, cultures, ages and times. It is better to get lost in translation, than to miss the book.

I recently became a volunteer member of the TED Translators team, translating subtitles for TED and TEDx Talks. So far, it has been no simple task.

Comments

Post a Comment